Vanessa Walters’ The Nigerwife (Masobe, 2023) is, amongst other things, a novel about dreams. On each page, old and new dreams collide seamlessly in tidy, unhurried prose; while her characters prod us to ask: when is it enough to stop dreaming? Or to what extent do we reach to accomplish it? We are not granted resolutions to these questions, however, but plunged into lustful text to nurture our remote hours of inquiry and enlightenment.

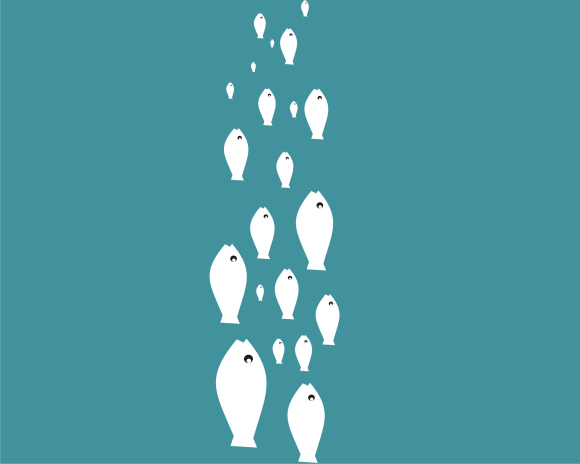

It starts with a hair-raising preamble; we encounter a woman called Nicole wondering what had happened to a body. We read that, “A few months after she arrived in Lagos, a body appeared in the lagoon close to the compound, bobbing along in a blanket of trash, a bloated starfish facedown in the water”—a body so suffocatingly near “she could have reached it with a pole”; a spot-on simulacrum of the city’s inventions and carnivorousness. What is known is that there’s a dead body and Nicole is snagged in a nuptial reel with a man she’s frightened of. But what remains unbeknownst is whether the dead body is the root of the tale’s serpentine mystery.

Walters is a powerful guide. She tows us through varied porters of knowledge employing a meticulous eye for detail and an attentive ear for descant language. For her, knowledge is never the grain of arrival but an apparatus for discovery. Does it matter if, in attempting to cultivate the background of the story, she leaves browbeaten, over-descriptive, hyper-performative morsels lying about? Or whether they make us feel worn out this second and the next second ripple our curiosity into a wild, unabating fever?

It’s the noughties. The story is set in the melodramatic city of Lagos. It spirals around Nicole, a UK law-graduate-turned-housewife who relocates to Nigeria with her family to escape an overwhelmingly dark past. Her husband is Tonye Oruwari, a Nigerian hotshot from a mega-rich family that inhabits one of the “waterfront mansions with its swaying palm trees, sparkling swimming pool, and verdant garden” in Victoria Island. They reside in their parents-in-law’s house with their two sons, Timi and Tari; Tonye’s obsessive parents and two sisters; and an off-kilter cluster of skivvies and majordomos who worship the Oruwari family like pantheons.

From a vantage, Nicole has a stunningly flawless marriage, but as we leap forward, closer, page in, we glean that all the glittering rocks are mere camouflage for the pestering leaks and shadows in her seemingly picture-perfect matrimony. On one occasion, she discovers a plastic package and a hotel receipt in Tonye’s custody. “The image on the packaging showed a woman in lacy underwear and silver leather hooker heels lying on her tummy with her wrists and feet tied taut behind her, making a bow out of her body.”

In coming to Lagos, Nicole wanted “a different life.” She yearned to be “an international lawyer, earning tons of money and travelling the world.” But she had to squelch these under her husband’s redeeming altar. Things go on fairly well—plus to some extent the Nigerwives Association stood ever-present as a community to validate her self-denials, reminding her “what it was all for.” This was until Tonye began to fail her—from the arrant remissness to the odd late-night appointments, and then the package discovery—prompting those repressed dreams to stew over. So for the first time since their marriage, she’s made cognisant of her tediums, her deprivations, her estrangement.

As a consequence, Nicole’s estrangement demands that living in the moment slowly gets superseded by escaping it, which angles out in the future to be her most intimate doom. The wheel rolls on. A throng of secrets wave their roots in the fictional wind. Morality is flung out of the window like a bad preoccupation. Love turns into caution. She plunges into a lukewarm, complicated love tryst with Elias whom she met during a boat trip. She discovers Tonye has been sleeping with her titular best friend; she is irate and devastated; she disappears on a rain-washed Sunday morning.

READ MORE REVIEWS

Her disappearance proceeds as the ultimate mirror on which the entire novel is reflected, a conspiracy of many conspiracies. On each page, a driblet of question markers: Is she dead, or alive? If dead, by whom? If alive, how and where? Walters conveys to us the unknown with the dexterity of adept hunters who relish the chase more than the kill. “The questions become characters,” as she said in an interview with Audible, “and the questions become places.” We are not simply bystanders in this journey but also invested components of the design. We see ourselves suspended in a swinging world of paradoxes and uncertainties where everybody is suspect. Perhaps it is her tone: brilliant, pity-soft, autobiographical, non-judgemental; perhaps it is her uncanny ability to transpose experiential certitudes into the fictional space (she was a Niger wife living in Lagos for seven years). Or perhaps it is the self-regulating way the narration is split between two thresholds of view—Nicole’s, and her estranged, do-it-yourself aunt, Claudine, who traces the former’s ghost throughout the book—creating a two-party character perspective.

If Walters has anything amiss, it’s mainly her curious distrust for readers. She knows too much and wants us to know too much. She doesn’t sway our attention by devising needless lacunas for readers’ fill. She constructs the story so believably true to the point of hyperrealism. While embellishment is the essence of thrillers, The Nigerwife has none other than a blatant sense of obligation to tell the story as it is. Or should be. Lagos is as real as ever: the muddying rain, the glittering streets, the crammed populace, and the extreme upper-class culture. In the same beat, Claudine who administers the detective function in the novel is just like us: ordinary. She cannot smell wrongdoers from half a mile away or analyse one hundred and sixty separate ciphers like Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. She’s an everyday woman who raised Nicole when Nicole’s mammy died of drug abuse. Her only skill is assiduousness. Yet it is through her pointedly sapient wanderings that we learn about Nicole’s childhood adventures and the seemingly probable suspects in the unwinding tangle.

What’s most striking is how the novel looms beyond a single-trope story about a South London woman snagged by a defiant urge to replace old, boring dreams with fresh, exciting ones. Rather, Walters capitalises on Nicole’s story to remind us of our human commitment to our clan, our community, and more still, those tender, hungrier selves within each of us. Although, guilt appears to be a missing trait in the novel’s imperious characters, we cannot neglect the stark account of the repercussions of discontentment and infidelity. For one thing, Walters’ superpower dwells in her capacity to withhold the truth because we never completely know the magnitude of that wreckage, even though we know how it came to be. Questions abound, pending: Will Elias’ destiny fare well after his disappearance? What happens to the Oruwari household once the news eventually goes viral?

Even the epilogue doesn’t roam far from the tree: Nicole isn’t dead—she wakes up on an incognito island with an amnesic brain. Walters brings us to this climax slowly, and calmly, like an afterthought. Like magic, our suspicions are exonerated and there’s no dead body count. Except it is an amalgamation of unhappy happy endings—reminiscent of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice or Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day—where we witness a character’s outer life, to quote Natalie Jenner, “remain the same, or worse, diminished from what it was. Who perhaps learns their lessons in life too late.” Take Nicole as a case in point. She finally escapes, but to what? And even if she locates her way home, what life remains?

Do we care about endings, especially the happy ones? Affirmative. No. It depends. Besides, life isn’t an architect of happy endings. But when we think about it, quite intensely, what we crave the most—in Natalie Jenner’s words—is “an ending that gives us hope, no matter how middling. Hope that it is never too late to change, that all growth is worthwhile, big or small, and that life will never give up on us, as long as we don’t give up on it.” The Nigerwife may not offer us that particular kind of hope but it fills us with evidence that hope exists, whether or not we acknowledge it. That’s why when we switch off the blue lights and step away from our reading desks, the photograph still hanging on the perimeters of our minds is that of a lady rising out of the lake. Isn’t this how we know we have been immensely entertained?♦

____________________________

Njoku Nonso is a Nigerian Igbo-born writer. His work which explores the self as a unit of language, familyhood, spaces, death, grief, and otherness, has been published in Boston Review, Chestnut Review, Agbowo, Bodega, 20.35 Africa, and Ake Review.